Like many young people nowadays, my first encounter with Angela Carter was in University. My second year literary theory class had The Bloody Chamber on the reading list. At the time, I didn’t think too much beyond ‘here’s something for me to read for uni’. When I read it, I thought it amusing – gross but ultimately very funny. (Having not gone to Literary Theory for some time, I missed out on the gender classes and didn’t get a lot of the stuff). Then I grew up (and by grew up, I mean I chose to study English ‘for real’). Angela Carter was referenced a few times in various classes and I thought to myself ‘Aw yeah, her that wrote that book for lit theory’.

End of third year dawned and we had to hand in our dissertation proposals. I outlined a study of early science fiction stories. At the airport to go on holiday, I wandered into WHSmith and picked up a few books: Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Dara O’Briain’s very funny book whose title escapes me at the moment and Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus. I came back from holiday and changed my dissertation topic.

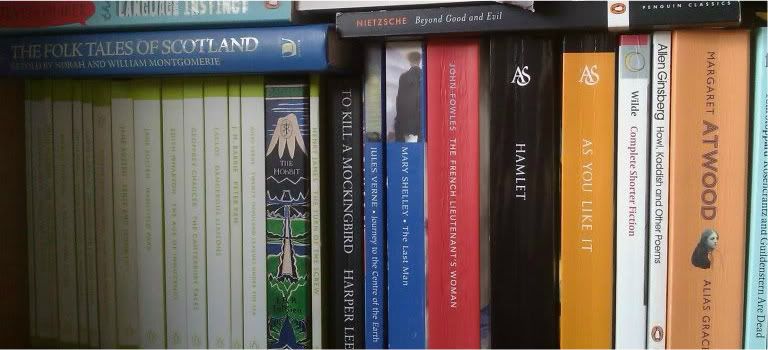

Since then, Nights at the Circus and many other Angela Carter stories have made their way onto (and off) my reading list. I feel, in a sense, like I’ve started my own little Angela Carter cult – my book collection could certainly be seen as a mini Angela Carter shrine. Still, though, Nights at the Circus remains my favourite of the lot (which is surprising, considering how much work I put into it for my dissertation. Perhaps that’s why I like it so much? Who knows, but like it I do.)

Nights at the Circus has become synonymous with gender studies. I think my advisor’s words were that my choice was rather predictable. I don’t disagree – the plethora of writing on Nights at the Circus probably amounts to quite a few rainforests and I don’t imagine there is any avenue left unwalked when it comes to theory and interpretation – and there’s a reason for that. A neo-Victorian text that confronts and subverts gender roles, deals with Marxist feminism, Foucault's panoptic prison, lesbianism, compulsory heterosexuality… the list goes on. And on.

But it’s not just for the theory that I love Nights at the Circus (though the theory in it did make me reconsider my view of Jane Eyre’s Mr Rochester so much that, in my dissertation, I called him a prostitute – but that’s for another day). Carter’s prose is very, very funny. In Nights at the Circus, the humour is evident from the get go – Fevvers ‘lets a ripping fart ring around the room’. She’s gawdy, false, eccentric, she subverts the readers expectation of the chaste princess so readily that our heads are left spinning for a bit while we catch up with the fast paced monologue. The Bloody Chamber compares a vagina to a ‘split fig beneath the great globes of her buttocks’ – an image so absurd and so vivid that it cannot help but draw startled laughter from the reader. In Nights, the male protagonist becomes a human chicken and needs to be rescued from the homicidal Buffo the clown. If you can’t laugh at that... Well, as Makinen states "the savagery with which she can attack cultural stereotypes [can be] disturbing."

Nights at the Circus is also a love story. Walser falls for Fevvers. Does he love her? It’s never made clear that he does, nor that he doesn’t. But he does join the circus to follow her and even he himself cannot deny that she ensnared him. This “chatty, down-market” (Michael) giantess of a woman can be loved – and by a ‘professional’ American. It warms the heart, in a way.

But as a reader you cannot help but be aware that Carter is trying to teach us something. Or, at the very least, that she is making us consider something that, without the subversive nature of Nights at the Circus we never would have. Lizzie’s interjections about marriage (“Pah! Out of the frying pan into the fire! What is marriage but prostitution to one man instead of many?”) and the constant reminder of Fevvers’ job as a ‘chaste’ prostitute are like hammers to an anvil – thou shalt not forget that the two lead females are not the typical female leads.

There are so many to say about the subversive nature of Lizzie and Fevvers but this isn’t my dissertation, it’s an Angela Carter Appreciation Post.

Like Nights at the Circus, Black Venus (another neo-Victorian text) is amusing, even as it deals with serious issues of gender and race. The split narrative voice creates Baudelaire’s Romantic, aesthetic ideals as he watches Jeanne dance for him but the switch to Jeanne’s perspective shows how ridiculous those thoughts are and grounds the images in stark reality. It’s amusing because it shows the lack of understanding between Jeanne and ‘Daddy’ and shows the lack of ‘realism’ that poetic language causes. In one sense, Jeanne breaks through the poetic language and gives the reader greater access to the text as we tend to agree with her views (yeah, exactly, Jeanne – snakes don’t dance and if they did, it would be nothing like how Jeanne is dancing for Daddy). Is this not only a short story on gender and race but also on the absurdity of poetic language? Like with Fevvers, Carter does not let us forget that is a prostitute and the relationship between money and sex is brought up over and over again. Perhaps the most amusing (and subversive?) thing about Black Venus is that Jeanne considers her relationship with Baudelaire purer than any of the others because he pays her. Isn’t that a paradox?

There are problems with Angela Carter’s work, though. Her work is so laden down with theory (The Magic Toyshop, for example) that it can exclude a wider readership – her novels are, in a sense, too ‘high-brow’, despite their vulgarity and humour and their ‘low brow’ characters. One could read Nights at the Circus and come away not understanding even half of what is going on behind the scenes. Does this change the way that Carter is read? It must, surely. It certainly changed the way I read Angela Carter: her tales went from being amusing little versions of popular fairy tales to subversive novels on gender, relationships, homosexuality, politics...

Still, when asked for a book recommendation, Angela Carter is still the first author to spring to mind. What book? You might ask.

I answer: all of them.

No comments:

Post a Comment